I wasn’t planning to go out of my way to see Hamilton. It had been so overhyped that I was sure I’d be disappointed, and the one I time I’d tried to listen to a few songs of the soundtrack, they hadn’t really grabbed me.

But 8 months ago, a friend somehow managed to get tickets and I think I’d had a few drinks when he said, “Do you want tickets for December 20, you have thirty seconds to decide” and I impulsively said yes.

December 20th eventually came, despite the world’s best intentions, and up until the last second I thought of selling my ticket or giving it away. But I went.

The first few songs I was like, “Oh, this is pretty cute, sort of like Schoolhouse Rock, but maybe more fuss than was needed.” And then there was a song In Act 1. No spoilers, but it’s 11 songs in. And I almost literally stood up.

And then it just kept going like that, with my jaw dropping more and more, with tears eventually, and anyway – not to overhype it… but it wasn’t overhyped.

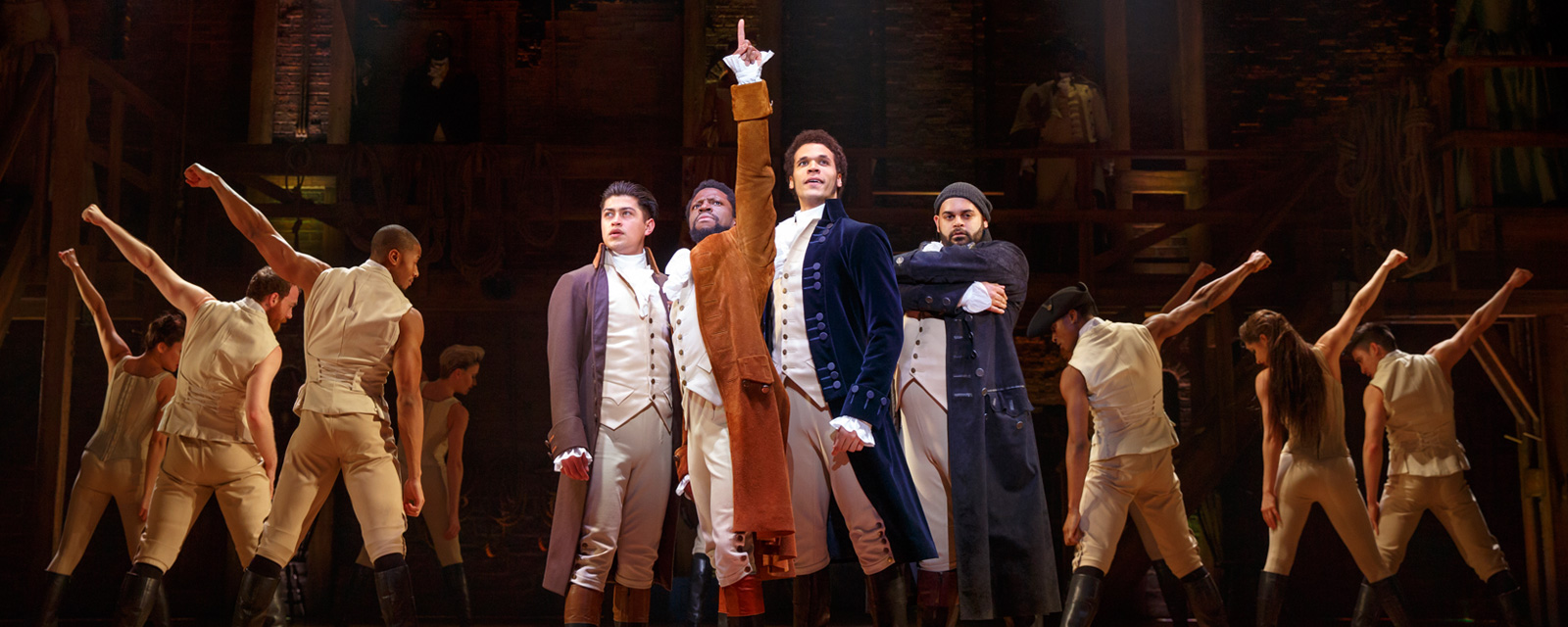

via Hollywood Pantages

But of course the whole time I was watching it, I was noticing what about it worked so well, and I wanted to share a few observations.

1. Lead with people, not with plot.

There’s a lot of plot in Hamilton – wars, rivalries, betrayals, weddings, deaths. But behind all the rap battles and the duels, the heart and soul of the show is the characters and their relationships.

We may have never led an army into battle or ran for president and fought in a duel, but who hasn’t been the Angelica to someone’s Eliza? Who hasn’t been the Burr to someone’s Hamilton? Who hasn’t been the Hamilton to someone’s Washington? These are characters and relationships we understand because we’ve seen them, we’ve lived them – and watching them on stage helps us understand ourselves.

2. Don’t be afraid to reinterpret history.

I enjoy period pieces as much as the next BBC aficionado, but it’s frustrating that the entire cast is often white, straight, and cisgender, and very often also men. When directors are asked about this in interviews, the understandable excuse is usually, “Well, that’s how it was back then!”

Something amazing about Hamilton is that it stays true to the heart of the history and the characters (sort of) while rejecting the idea that all of these characters should be white. Even better, it’s more than just “colorblind casting” (an old term sometimes used when an actor of color is cast in a role written to be white, as well as the reverse) which is problematic when it erases the real differences in people’s lived experiences. Instead, the show actually brings those experiences into the text and the production.

I also personally dislike “based on a true story” stories (it’s been a rough few years for me at the cineplex) because it usually feels like the writer did years of historical research and then felt she had to shoehorn every single fact she learned into the script so they wouldn’t go to waste. The stories feel bloated and boring and often kind of confusing, because real life rarely follows a clear story arc.

Something I appreciate about Hamilton (that some historians likely do not) is that Lin-Manuel Miranda altered, embellished, or straight up invented several plot points in the play to fit the larger narrative he was trying to tell. That might make for bad history books, but it makes for better stories. As an audience, we get the capital T “Truth” (the heart of the story’s meaning) without getting bogged down in the lowercase t “truth” (a complete accounting of provable facts).

3. Give every character a distinct point of view.

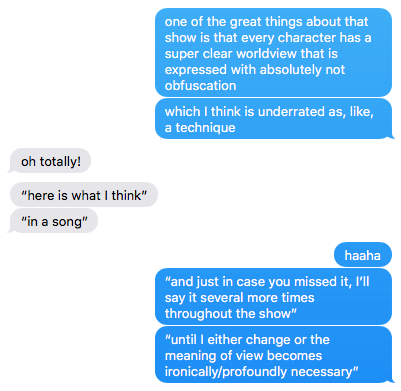

I had this text message exchange with my friend Anna the morning after seeing Hamilton:

Every character in Hamilton has a distinct worldview. Hamilton thinks it’s most important to be bold, take chances, speak your mind, and jump into the fray. Burr thinks it’s best to keep your opinions to yourself, play both sides, and look out for #1. Eliza thinks there’s no point to liberty if not to enjoy it beside the people you love. Angelica thinks romantic love can never satisfy so there’s no point in prizing it above other things. Jefferson, Washington, and even King George have similarly clear perspectives.

These worldviews aren’t something you have to work hard to interpret; the characters literally speak the beliefs and values they hold most dearly and they say them multiple times throughout the show. The complexity of character comes from how those perspectives play out when characters are put in situations that challenge their values and beliefs, and when they are pitted against (or are forced to be allied with) characters who have opposing values and beliefs.

Some characters eventually change their minds, at least a little, over the course of their character arc, while other characters never change but instead their views take on an irony or a poignancy in light of events of the story, but all of the characters’ central worldviews are relevant to the themes and plot of the show, which is why they feel resonant to the audience.

***

You can now like this page on Facebook! Click the “Following” dropdown and select “See First” and “Notifications On” to get notified of new posts.